A common saying often passed around in cinephile circles is that “every movie is a miracle”. The process of creating films — no matter how close to the bottom of the barrel the final product that audiences get to see ends up — is so arbitrary, intricate and riddled with risk that the chances of a feature making it to the finish line at all is cause for celebration and awe. For every movie that hits the theatre, dozens if not scores got lost in the labyrinth that is industry networking somewhere along the way, or stumbled an early grave navigating the mire of production. Film-making, by its very nature, is a collective effort. It doesn’t just need people with an artistic vision and the skills and talents required to bring that vision to life like all other forms of art do, it also requires people to manage, distribute and market their creative efforts, let alone make sure they actually go rewarded. It’s a complicated clockwork machine, in which the slightest missteps can have massive repercussions, and it probably won’t surprise you to hear that if you add animation into the mix, the challenges facing your production may as well increase exponentially.

Suffice it to say, then, that if every movie is a miracle, every anime is a divine revelation. Anyone who’s seen Shirobako, P.A. Works’ multifaceted and often nerve-wracking delve behind the scenes of a floundering animation company knows that the anime production process is to the Hollywood pipeline what a leisurely stroll to the corner shop is to a go at a new record on American Ninja Warrior. Deadlines are tight, budgets are tighter and lead times might as well not exist. Animation studios and their employees live from one project to the next, barely holding on by the skin of their teeth as they patchwork the efforts of the handfuls of freelancers willing — or desperate enough — to squeeze in another few hours of overwork into finished episodes often mere hours before they’re supposed to go on air. Seasonal anime is a market that is both dangerously crowded and extremely volatile, in which you either strike while the iron is still hot, or risk a flop so catastrophic dozens of people end up losing their livelihoods. Squeezing any sort of profit out of producing anime therefore seems like a challenge only a fool would take on — yet wherever economic challenges rear their heads, game designers are paying close attention.

Economic simulation board games have a lot in common with seasonal anime. A ton of them are made every year, but not a lot of them make enough of an impact to be remembered. Most economic board games, like most seasonal anime, reiterate on established mechanics and tropes that are old enough to drink at this point — worker placement, resource conversion, engine building; you name it — leaving theme as the one true arbiter of which games become staples and which get relegated to the bargain bin. Any old game smith worth their salt can design a satisfying way for you to turn cubes into currency; but very few of them can make you truly believe that you’re trading spices at a bazaar in the Middle East, financing a larger enclosure for your ever growing collection of rhinos or hastily selling all of your stock in canal transport when railroads turn out to be the future. This, of course, begs the question. If a board game wanted to successfully simulate the anime production process, how would it have to go about it? Which specific intricacies that set making anime apart from — say — oil production or car manufacturing would this game have to nail? In other words, what sets “an anime series” apart from any other economic product?

In my opinion, any halfway decent answer to this question would have to keep in mind the following three key characteristics of anime production:

- Making anime is hard, and making good anime is even harder. Any game looking to simulate this creative process would therefore have to give players the feeling that the anime they produce — and consequently, the rewards they get for doing so gain in the game — didn’t just fall into their laps through no effort of their own.

- Making anime is a team effort, and results from a complex web of often deeply hierarchical interactions between various stakeholders with diverse interests. Any game looking to simulate this creative process would therefore need to acknowledge that many people, each with different talents and responsibilities are responsible for delivering a finished product.

- Making anime is making art, and is contributing to a kaleidoscopic creative tradition with near limitless potential. Any game looking to simulate this creative process would therefore have to allow or even incentivise players to create unique works that reflect the distinct circumstances they were produced under.

Of course, I’m not talking about hypotheticals here, and this shouldn’t surprise you. Of course there is a board game about anime production already. There is a board game about everything. Last year, Esper Game Studio released the first edition of Jisogi: Anime Studio Tycoon, designed by Rodrigo Esper, with art by Eisuke Go, Senkawa Teien and whole host of guest artists, including Code Lyoko and Basquatch creator Thomas Romain. It’s exactly what it says on the tin, a board game that claims to be based on “the real stories, struggles and personalities of the people who give their blood to make our favorite Anime come to life”, created by a team “with strong connections in the Anime industry” who have consulted “producers and artists from many studios”, including Star Wars: Visions producer and Studio Trigger trustee Will Feng and Production I.G. alumna Yumiko Yoshizawa, who worked on B: The Beginning, Blue Spring Ride and the FLCL sequels as a production assistant. According to the blurb on the back of the box, Jisogi invites players to “run their own anime studio, dealing with a tight budget, traumatised staff and looming debts”, and to “seize trends, capitalise on business opportunities, and recruit eager new talent to turn their studio’s fortunes around”. Sounds charming, and made with clear love for the industry, but does Jisogi actually manage to make its players genuinely feel like they’re making anime, or is this yet another abstract efficiency puzzle with a fancy coat of paint? And, perhaps most importantly, is it any fun to play? Let’s find out.

In Jisogi, up to four players take on the roles of new managers at one of the upstart anime companies risen from the ashes of a massive bankruptcy. In an example of jitenshasōgyō, a business practice defined in the game’s manual as “barely keeping a business going by using funds from previous projects”, and to which its owes its title, players will have to use what little funding they have to produce and promote new anime series, pay off their debts, give their burnt-out staff back the will to live and compete to be the one studio that will go down in history as having instigated a “new wave of Japanese animation”. Whoever manages to gather the most resources and most effectively funnel these into the production of the right anime at the right time, will earn the highest number of reputation points, and win the game.

So, how do you play? If you’re familiar with the concept of a “worker-placement game”, Jisogi should look pretty familiar. In a worker-placement game, every player has a set number of actions they can perform, represented by a worker pawn that needs to be put in a certain location on the game board in order to carry out the corresponding action. In Jisogi, however, each of the four workers you start the game with — represented here by cards and tokens rather than pawns — have their own specialities limiting which spaces on the game board they can be sent to. Writers and animators mostly exist to help you gather resources, while your production assistant is the only worker that allows you to hire additional workers, and as such, increase the number of actions you can take on a turn. Finally, directors are the obligatory wild-cards among your workers, and can be sent anywhere to do anything. Now usually, worker-placement games will operate on a first-come, first-served basis. In other words, when one player’s worker has seized a certain spot on the game board, no other player will be able to take that same action. In Jisogi, however, that is not the case. Even when another player’s writer is hogging that precious “research” action space, you are allowed to place your token there — albeit for a small fee. This is supposed to represent the anime industry’s heavy reliance on freelance labour. In theory, you can pay anyone to do any job for you, that’s for sure, but since talented freelancers are in high demand, you’re likely not going to enjoy how much it’ll cost you. In Jisogi, players will be quick to learn that lesson when their budgets at the beginning of the game are as tight as a Victorian corset.

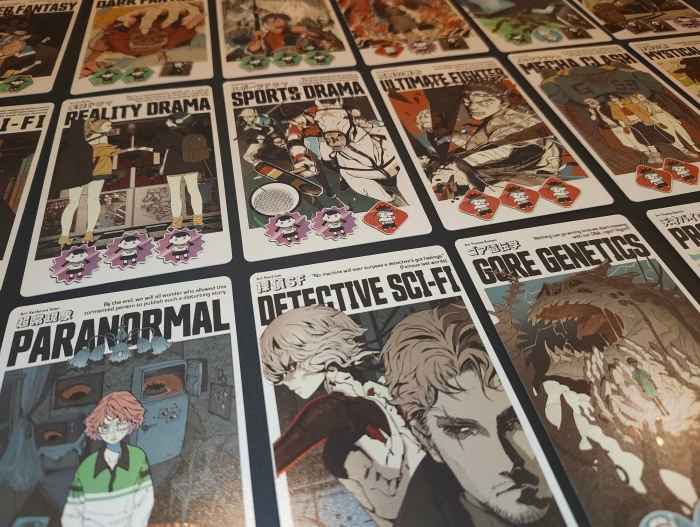

Enough about spending money, though. How do you make it? By releasing high-quality anime, of course! To put your studio’s latest masterpiece out there — which you can only do at the end of each of the game’s four rounds — you’ll first need to gather the three parts that will make up your script. These are adorable little cardboard tiles describing either a setting (e.g. “cyberpunk megacity” or, of course, “high school”), a general plot (e.g. “an alien ship crashes on earth” or “the lone survivor of a massacre seeks power to defend the weak”) or a unique twist on a formula (e.g. “the prophecy was heavily misinterpreted” or “a cult is secretly manipulating their lives”), which players can acquire through game actions carried out by writer tokens. While the text on these script parts is mostly there for flavour, the colour of these tiles does matter. There are five in total, each representing the conventions of action, fantasy, sci-fi, horror and slice-of-life anime, and a player who manages to assemble a full script out of parts in the colours matching those on one of the three currently active, gorgeously illustrated “trend cards” (e.g. two parts action, one part fantasy for an “isekai power fantasy”) will be rewarded far more exuberantly than a player who insists on putting out a sports drama in an industry where supernatural rom-coms are all the rage.

It’s here, however, that Jisogi shows off one of its most magnificent feats of thematic resonance. If a player ever assembles a script of which no part matches any of the prerequisites on the currently active trend cards, they can opt to release it as a “cult classic”, eschewing the raw quantity of reputation points you get for following trends in favour of a massive multiplier on any additional bonuses you may have racked up during production. This mechanic perfectly encapsulates anime’s ability to not just follow trends, but create them as well, and shows that artistic vision and prowess are ultimately able to trump market demands, as many of these bonuses are can only be unlocked by bringing in talented and experienced staff, or by making sure that your anime is not just written well, but nice to look at too. Additionally, artistic credibility is a literal resource in Jisogi, and can be gathered from spaces on the game board exclusive to artist workers. At least one token of this resource is required to turn a finished script into an actual anime, but more may be added for the aforementioned bonuses, opening players up to various strategies. Do you churn out one middling, but guaranteed mainstream hit after another, or do you focus on quality over quantity, building up a loyal fanbase at the expense of a consistent release schedule? It’s a conundrum that casts anime as art first, and product second, acknowledging both the difficulties of making it and the ways in which doing so regardless will often be rewarded in the end.

This doesn’t mean that making an anime series that will go down in history in Jisogi is easy, however. At the start of the game, players only have access to “burnt-out” staff — whimsically represented as harrowing spectres — who can only perform the most rudimentary version of each in-game action. The only way to trade in a depressed worker token for a more chipper one — referred to in the game as “genki” — is to put your money where your mouth is and give them a much-needed promotion. Genki workers will demand a higher wage during each round’s upkeep, but they power up whichever action to assign them to carry out for you, and players who refuse to take care of their workers’ well-being will be locked out of certain precious resources entirely, such as “merchandise deal tokens”, which boost your company finances, and “hype tokens”, which can be exchanged for any other in-game resource at varying rates. Furthermore, promoting a staff member — or coughing up the funds for a brand-new one, as new hires are genki by default — will unlock their specific proclivities and abilities, eventually allowing players to assemble a distinct line-up of kooky characters that grant unique boons. With these characters, Jisogi shows its attention for detail and love for the rich world of anime, as each unique genki staffer represents a particular anime character archetype or, in some cases, even directly references an iconic creator, like a Junji Ito stand-in who provides bonuses only to the darkest of horror anime and the fluffiest of slice-of-life, or a contrarian who benefits from bucking trends who bears an uncanny resemblance to Guillermo del Toro.

Then again, there’s not much of this joyous creativity you’ll get to see or enjoy if you don’t get your finances in order. Getting anything done in Jisogi will require you to part with your hard-earned cash, and if ever you have to pay for an action or a worker salary when your coffers are empty, you will be forced to take a so-called debt card. Debt cards will give you the money you desperately need, but unless you get rid of them by the end of the game, they will reduce your overall reputation during the final scoring round. Oh, and there’s interest, too, so you had better pay of these debts sooner rather than later if you don’t want to end up like Gainax. The debt mechanic is the cherry on top of Jisogi‘s design, turning what is in theory a breezy engine builder that incentivises players to just do whatever feels right to them into a desperate struggle for survival, especially if you pay with the additional rule that starts each player off with a debt card already in play. It’s a surprisingly cruel mechanic in a game otherwise oozing with passion and whimsy, but a necessary one, teaching players that the anime they enjoy doesn’t just spawn out of a pit in a magical forest somewhere at the foot of Mt. Fuji. The manual even contains a note explaining that Jisogi “was created to emulate the hard truth of running a company with a limited budget and low-profit [sic] margins”, though it does leave space for play groups to skip the interest increase “if your group isn’t comfortable with the concept of debt or might feel overwhelmed by the pressure of rising interest rates”.

It might seem a little bit strange for a board game to undercut a fundamental aspect of its design like that, but in the context of the broader discourse the board gaming space has seen in recent years — in which publishers have come to realise that their products are inherently political statements no matter how light-hearted the actual design might be — it makes sense. The trivialising or even gamification of real-life atrocities committed in the name of cold hard cash, seen in many economic simulation board games like Puerto Rico, Maracaibo or even perennial classic Settlers of Catan has come under scrutiny, leading to a number of critical re-evaluations. Puerto Rico attempted to decolonise itself by updating its setting to after Puerto Rican independence, Maracaibo released an expansion all about the slave uprisings in the Caribbean and the latest versions of Catan quietly dropped the loaded term “Settlers” from its title. Furthermore, we started seeing more and more newer designs that put an explicitly anti-colonialist spin on classic formulae, most prominently Cole Wehrle’s John Company and the entirely co-operative, if somewhat cheesy liberation fantasy of Spirit Island. Now, obviously, Jisogi doesn’t deal with colonialism, but it does, of course, deal with an industry rife with other forms of greed and exploitation that shouldn’t just be ignored.

Knowing this, Jisogi‘s decision to make its harsher mechanics entirely optional may read as “virtue signalling” to some, propping up the debt cards as a reckoning with the harsh realities of the industry it seeks to represent so uncompromising casual players might want to opt out, just to throw potential critics a bone. I think this would be entirely too cynical of a judgement, though. From the art to the flavouring on the various cards you play during the game, Jisogi radiates love for the craftsmen and -women behind the scenes of the anime that inspired it, even remembering to include unsung heroes like press liaisons, PR reps, in-between artists doing outsourced busywork and company accountants as vital parts of the production process. Sure, there are references to the ills plaguing the industry all over the place — shareholder greed, questionable funding and indeed, piles and piles of debt — but Jisogi weaves these into its world as a reflection of the reality these artists have to reckon with, rather than tempting its players to revel in them with nary a thought, all for the sake of their bottom line. At any occasion, Jisogi urges its players to empathise with their workers by doing things few other worker placement games do. It gives the pawns identities, faces and quirks. It encourages players to prioritise good labour conditions over exploitation, making rewarding your staff for their talent and boosting your reputation rather than your profits fundamental game mechanics. It even educates players about the benefits of offering your workers the opportunity for an exchange program, a convention appearance, or on-the-job training. This game won’t teach you how to run a company, but it might just teach you how to run a company well.

Suffice it to say, Jisogi passes the standards I set at the beginning of this article with flying colours. It acknowledges that making anime is hard, by forcing players to go into debt and skimp on art tokens during the first few rounds of the game, hammering home the point that great things can only come from small beginnings, and that anime is not an industry that will turn graphite on paper into gold just like that. It acknowledges that making anime is a team effort, by eschewing the generic worker pawns you get in so many of these games in favour of specialist workers, each of which with their own quirks, and paying homage to the many hands that touch a production before it hits the screens, while still acknowledging that the artistic chops that supremely talented individuals contribute can often make the difference between a good anime and a great one. Finally, it acknowledges that making anime is making art, mostly by being itself a work of art, stuffed to the brim with memorable illustrations and rife with knowing winks to the audience, but also by paying meticulous detail to the myriad factors that make each anime unique, as represented by the stunning trend cards and the flavour text on the script tiles. As far as thematic resonance is concerned, Jisogi is going to be very hard to beat if anyone else ever wants to have a go at making a board game about running your own anime studio.

Will board gamers get what they are looking for here, though? That’s a different question altogether. With the kind of game is is, Jisogi seems eager to compete in the big leagues, alongside universally beloved juggernauts like Brass: Birmingham, Ark Nova, Agricola or any of the dozens of other economic simulators in the BoardGameGeek Top 100. Unfortunately, however, I don’t feel that, if you strip Jisogi down to the core mathematical puzzle of the centre of it all, it holds up compared to any of these beloved brain bogglers. The lack of player interaction — blocking off worker spaces on the game board is essentially the only way for you to get up into other players’ business, and even then, all you’ll do is force them to pay an additional fee — means players looking who come to board games strictly for the competitive or the screwing-over-your-friends element will likely lose interest quickly. Furthermore, whereas many other games will offer players a variety of pathways to victory, or a wide range of choices in which mechanic to specialise in, Jisogi forces every player down the same trajectory, often making it so that repeated plays will follow the same general structure, and the difference between a victory and a defeat will likely stem from a combination of miniscule decisions and a healthy dose of luck, as opposed to any grand strategy or the ability to crunch harder than anyone else at the table.

The question is, however, whether any of that matters at all. Leaving aside the crème de la crème of the genre, most economic simulation board games are entirely interchangeable when you consider them inside a vacuum, and the market for these kinds of games is so saturated that a true revolution is becoming harder and harder to find. Luckily, games don’t have to exist inside a vacuum. They are more than a series of interlocking mechanics you try to unravel in an attempt to prove yourself intellectually superior to your opponents. Heck, if that is all games could be, we’d all still be playing Tic-Tac-Toe or Pong, and this hobby wouldn’t be nearly as big as it is. Games — even board games in all their relative simplicity — can be a catalyst for telling and creating stories, and few games do this better than Jisogi. It’s an experience first and foremost, in which the mechanics ultimately exist in service of the theme, rather than the other way around. Playing Jisogi is not a cut-throat battle of wits some may be looking for, but it is a shared celebration of an industry that continues to fascinate entire generations. Hardcore gamers chomping at the bit for something they can get to the table every weekend probably won’t find what they are looking for here, but if you and your friends love both anime and board games, and have at least a passing interest in what goes on behind the scenes, Jisogi: Anime Studio Tycoon is exactly the game you’re looking for.

Esper Game Studio are currently running a Kickstarter for a widespread release of Jisogi: Anime Studio Tycoon, and you have until March 5th, 2026, to help fund this release by pre-ordering your copy. Keep in mind that this Kickstarter is for a more affordable “retail version” of the game, which will not include some of the more premium components you can see on the pictures in this review.